It took me all day to make timpano, the special Calabrian pasta dish that serves as the (epicurean and narrative) centerpiece to Big Night, the 1996 movie co-directed by Stanley Tucci and Campbell Scott. “Dish” is too flat a term for what it is, which is really a drum—“a timpani drum,” in the words of its proud chef in the film. To make it, you tuck a flat sheet of pasta dough inside a round, 8” casserole pot, covering all the sides, and then you fill the pot with meat sauce, cheese, ziti pasta, meatballs, egg, and salami before folding the dough over the filling and baking it. Afterwards, you have a golden dome of cooked pasta that you slice and serve like a cake. It is crusty on the outside and soft on the inside—lasagna, baked ziti, bolognese, and spaghetti pie all in one.

There are easier ways to make it, shortcuts you can take—use pre-made sauce, dry pasta for the filling, and a food processor to mix the pasta dough—but this would not do Big Night justice. That film takes place in the 1950s, at Paradise, an Italian restaurant along the Jersey shore run by two immigrant brothers—and so I prepared my timpano the way they do: slowly, manually, devotedly. In the film, the timpano is the utmost demonstration of the film’s thesis: that good cooking is both an act of love and an achievement of art.

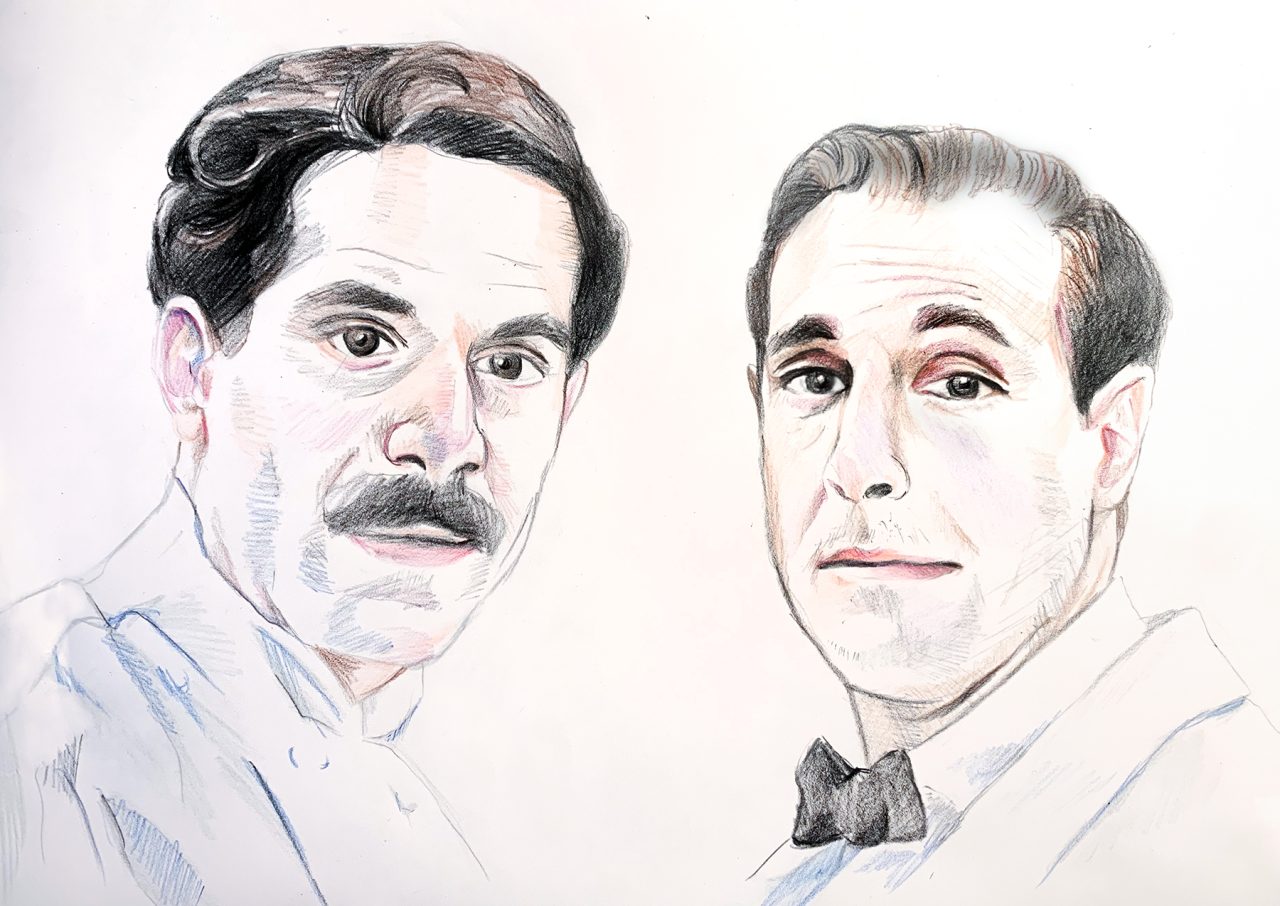

The film, which was written by Stanley Tucci and his cousin Joseph Tropiano, designs its conflict around food, with contrary sides taken up by the two brothers. The elder brother, Primo (Tony Shalhoub) is the chef—an artist, a craftsman who takes pride in sharing his ancestral homeland’s wonderful dishes. His younger brother, Secondo (Tucci), is a businessman and the restaurant’s maître d’ who is stressed about the restaurant’s financial future. Things do not look good.

In this time and place, Americanized Italian food is all the rage. Secondo exhorts his chef brother Primo to include popular dishes on the menu (like spaghetti and meatballs) and remove more alienating, authentic dishes (like his brother’s authentic seafood risotto) to attract customers, especially since a flashy red-sauce joint down the block has begun siphoning their clientele. Primo resists, with all his heart and soul.

And so the brothers are locked in a standoff, with Primo believing that the purpose of their venture is to bring Italian culture to America, and Secondo longing to allow American culture to influence their Italian food. They represent different facets of Italian-American identity, of cultural assimilation, and the immigrant experience in general. Is survival worth the compromise? Is capitulation a surrendering of values? Is it the brothers’ job to be ambassadors for their country? While Primo grows angry that their (few) clients expect sides of spaghetti and meatballs with every entrée, even his fine seafood risotto, he believes that this is correctable, an attitude born from ignorance. “Give people time, they will learn,” he assures his brother. Secondo responds that teaching Americans to appreciate Italian cooking is not their job: “This is a restaurant! This is not a f*cking school!”

Primo doesn’t particularly care if they stay in America; his relatives back home offer him an excellent chef job at a restaurant, where he will be able to cook his delicious food for people who understand it, who crave it. He doesn’t hate America, the way Secondo seems to hate the prospect of returning back home. He just wants to cook.

The brothers find a common mission when they begin preparing for a party that promises to turn their restaurant troubles around—a Hail Mary that’s almost out of nowhere. Pascal (Ian Holm), the proprietor of the swanky eatery down the street, promises that he will send his friend, the Italian-American musician Louis Prima, to eat at Secondo’s place, and so Secondo withdraws all their money and instructs his brother to prepare a feast to impress the celebrity and his entourage—a gamble he hopes will put their restaurant on the map. They invite everyone they know to the party—a six-course masterwork showcasing the magic of true Italian cuisine. It is the greatest night of their guests’ lives, and they leave transformed.

But it is in the preparation of this meal that the brothers truly begin to get along. Together—along with Secondo’s earnest girlfriend Phyllis (Minnie Driver)—they make the timpano. Timpano, wonderful timpano, a dish so technically complicated and conceptually regional that it seems almost impossible for Americans to comprehend—a dish many audience members might not have even heard about until seeing this movie.

Technically, the brothers make two timpani: one for their friends and one for Louis Prima and his company. And even though Secondo worries that it’s too labor-intensive, too long a process, he quickly gives in. The majesty, the magnificence of the timpano is too tempting an attraction for their great meal for even Secondo to downplay.

Together, they mix and knead pounds of pasta dough, stretch it and roll it, cut and press it. The camera pans over their workspace, their flour-dusted countertops, over the hands cradling the dough. There will soon be twin pasta dishes baking, and each timpano will wind up with a different fate—one celebrated for its greatness, one waiting forever for greatness to show up and anoint it. But for a moment, all the dough is part of the same thing, and the brothers are united in creating it. They are so united that, through the down-pointed camera, it’s unclear whose hands are whose—if we are looking at Primo’s hands or Secondo’s, holding, shaping, caressing the dough.

*

In 1974, the Italian journalist Vincenzo Buonassisi attempted to trace the history (rather, the histories) of Italian pasta making, producing at the end of his quest a 704-page volume entitled The Pasta Codex. In addition to anthologizing hundreds of regional recipes that might otherwise have been lost, The Pasta Codex includes a record of the references to pasta-style dishes throughout Italian history. The Roman satirist Horace wrote about the joy of eating laganum—strips of dough that were fried or roasted and served in soups, or with chickpeas and vegetables. The same dish, Buonassisi writes, was called laganon or lasanon in Greece, and became known as laganella in southern Italy. Laganella is still the term used in that region for the pasta we know as tagliatelle: the wide ribbon noodles that go so well with chunky sauces. Buonassisi notes how Apicius’s cooking manual De re coquinaria, included an extensive section about making casseroles from pasta sheets.

Tracing the history from the Middle Ages onward, he notes a document from 1279 (before Marco Polo came back from his trips) in which a Genovese merchant cataloged a crate of dried macaronis, and describes how, during the Italian Renaissance, the gastronomist Platina and the cookbook writer Cristoforo di Messisbugo wrote about the fad of sweet pasta: fried pasta dough adorned with cheese, honey, butter, and cinnamon. He writes about the fourteenth and fifteenth-century fads of drying pasta, and the development of tomato sauce in seventeenth-century Naples. So integral to the history of Italy is pasta, he avers, that it was developed in and evolved with the region throughout time.

The Pasta Codex dates timpano (or timballo) to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It lists 17 different types of “timballo” and four different types that are specifically called “timpano”—all regional. The big one is Timpano di Zitoni All’Impiedi, “the signature dish of high Neapolitan cuisine,” and it features prosciutto instead of salami, mozzarella rather than provolone, and a white, creamy besciamella sauce instead of Big Night’s ragu, with the ziti pasta all standing up, arranged like a crown. There are many variations that resemble the more rustic, golden cupola that Primo and Secondo make: some with peas, some with chicken, some with truffle, some that are almost exactly like the one in the film.

Big Night features Tucci’s own family recipe for the main dish. “Timpano (as it is called in Calabrian dialect) —or timballo—has been prepared for feasts and festivals in Italy for centuries,” Tucci writes in 2012’s The Tucci Cookbook—a co-production between his parents, Joan and Stan Tucci, the chef Gianni Scappin, Mimi Taft, and himself. “It is generally believed to have entered the lexicon of traditional Italian cooking from Morocco through Sicily. The Tucci family recipe was brought to the United States by Apollonia Pisani, my father’s maternal grandmother. She grew up in Serra San Bruno, a small hill town in Calabria.” Tucci’s father Stan writes in the introduction that Apollonia came to America in 1905, leaving her town Serra San Bruno along with her husband and children, and settling in Northfield, Vermont, a neighborhood that drew so many Italian immigrants that it was colloquially known as “Spaghetti Square.”

“I can’t remember when we had the idea to use timpano as the centerpiece of the Big Night meal, but I’m glad we did,” Tucci wrote. “Structurally and creatively, it gave us a strong focus for the meal and had repercussions that we never anticipated. During the first screenings we were amazed at the audience’s reactions to this dish. They were exactly those of the characters in the film—audible gasps of awe and wonder.”

In the film, the rival restaurateur, Pascal, screams when he takes a bite of the timpano. He shrieks and stands up, yelling “God damn it, I should kill you! This is so f*cking good I should kill you!” Primo’s food is impossibly delicious—both because of the passion with which he cooks, and the fact that he has invested his time in sharing the already-perfected recipes of his ancestors, rather than experimenting with his own creations.

The restaurateur Pascal is only concerned with his own success. His bustling restaurant is named after him, but Primo’s is called Paradise, an attempt to evoke a heaven which already exists—Italy. It’s clear that, as a careful custodian of his family’s gastronomic treasures, Primo is the rarer kind of chef in their milieu. When Primo suggests the timpano, though, he proves that he is also innovative: sharing something that the denizens of the sleepy Jersey town have never experienced before and will likely never experience again.

Primo accepts paintings in exchange for meals, brings leftovers to his friends at the Italian barber shop down the street. He doesn’t care about money. He is all heart. Shalhoub’s is a perfect performance: as balanced, substantial, and yet kaleidoscopically enchanting as one of Primo’s pasta dishes. He is sweet, stubborn, sincere, ardent, focused. “To eat good food is to be close to God,” he whispers to his date, the kindly florist Ann (Alison Janney). “I’m never sure what that means,” he adds, shrugging. “But it’s true.”

Secondo is hypnotized by the red neon lights and lounge singers at Pascal’s place, distracted while running errands before the big dinner by a Cadillac dealership. Tucci plays Secondo with determination, hunger, lust. He longs for the good life so much that he is blinded by its glare; he takes advice from Pascal, an obvious double-crosser, whose portrayal by the famously British (and British-looking) Ian Holm suggests that he might even be a charlatan. Note that the character’s name is not “Pasquale,” but “Pascal.” He is an impostor, with a vaguely—amorphously—European accent. He is a poser, a shapeshifter. “I am a businessman,” he tells Secondo only at the very end of the film, after he has been found out. “I am anything I need to be at any time.” He is Secondo’s false God, his Golden Calf. Primo worships honest food, and nothing else.

Indeed, the brothers have next to nothing in common. Secondo doesn’t know what he wants, and Primo does. Secondo is a little bit of a libertine (romancing both Phyllis and Gabriella (Isabella Rossellini), Pascal’s much-younger girlfriend); Primo is nervous around Ann. Secondo is invested in speaking English; Primo prefers to talk in Italian. Their incompatibility, inability to see eye-to-eye or even communicate well, is suggested by the first moment of dialogue in the film, when the two brothers are in the kitchen. Primo says something quietly, quickly in Italian, and Secondo says, harshly, “What!?” They chafe, they clash. Again: Primo is risotto, Secondo is spaghetti.

Spaghetti is not an Americanized food, per se—but it is the dish caught in the middle of both cultures. Secondo might be perturbed at the xenophobia of his boring American customers, but he is angrier at his brother for not catering to them. When Secondo trusts Pascal over his brother—gambling their money on Pascal’s promise to send the famous Louis Prima to Paradise Restaurant—he assures the restaurant’s failure. It’s Primo vs. Prima, and Secondo makes the wrong choice.

Notably, as Secondo insists to his customers, those two dishes, risotto and spaghetti (both starches, but completely different kinds) are never supposed to be served together. “Sometimes the spaghetti wants to be alone,” he sardonically informs a customer complaining at her risotto’s lack of a spaghetti side dish, which she expects because she thinks that at Italian restaurants, “all main courses come with spaghetti.”

Though they seem like complimentary figures, for their sequential names and bifurcated business partnership, Primo and Secondo are more than counterparts or opposites; they are too similar and too different in all the wrong ways. They chafe; they clash. They are, simply, brothers. This is the nature of the movie: not to find a way to serve the risotto and the spaghetti together, but to strip the brothers down to their common element. Like starch, they are both stiff, firm, gritty in their ways.

*

The climax of Big Night involves the two Italian brothers allowing their long-simmering conflicts to erupt into an outrageous fight, which makes sense because this is also, in a way, the story of Italy. In one of the myths of the founding of Rome, the brothers Romulus and Remus are surveying the hills to build their city. Romulus draws a line in the sand to mark where he will build his great wall, and Remus scorns it, jumping over it, attacking his brother. Romulus kills Remus there, ending the struggle about which brother’s vision will prevail.

Big Night seems to rework this old folktale. After the dinner party, Secondo goes looking for Phyllis, who caught him kissing Gabriella. Primo is in the restaurant, blissfully cleaning up after the stunned and staggering guests. It is late at night and early in the morning. As Pascal congratulates Primo on cooking his magnum opus, Gabriella forces Pascal to reveal that he never contacted Louis Prima—that Prima was never, ever coming. Primo runs to locate his brother to tell him about Pascal’s duplicity—finding him forlorn on the beach, with Phyllis dumping him.

Though Primo and Secondo were united in the dinner party planning, it is in the aftermath of this great meal that the brothers’ conflicting attitudes and personalities come to a head, exploding in a fight fueled partially by Secondo’s learning what Pascal has done: deliberately ruined him, to poach Primo and make him his new chef. Instead of getting mad at Pascal, though, Secondo gets mad at Primo, the messenger of this tragedy.

Presumably, Secondo is enraged because this proves that his brother—Primo, both a dreamer and a stickler— has been right this whole time. His brother has been right in his loyalty to his craft, and his love of his culture, and Secondo yells at him “You give to me nothing,” kicking at his brother in the air.

“Is that what you think? That I give to you nothing?” cries Primo, jumping at his brother, tackling him to the ground. The brothers wrestle, wriggle together. They never punch—they slap, they kick the air, they pull each other so tightly that they almost appear to be hugging. Their love is palpable inside their pain and fury.

Primo starts yelling at his brother in Italian and Secondo yells back in Italian. It is the longest conversation they have in their native tongue in the entire film; a sign that Secondo is finally giving up on America. A small crowd of concerned friends has gathered on the dunes, but the brothers’ fight is for their ears only. “Questo posto ci sta mangiando vivi!” Primo wails. (“This place is eating us alive.”) His brother angrily walks away.

But Primo chases his brother and pins down and begs him to sit still, yelling that Secondo has learned nothing. Then Primo collapses, laying down in the sand. “Vuoi che faccia un sacrificio, eh?” he asks weakly. (“You want me to make a sacrifice?”) “Il mio lavoro, muore, se sacrifice.” (“If I sacrifice my work, it dies.”)

At last Primo’s words get through. Primo’s purity, the thing Secondo loathes most of all, is the only thing left that matters by the end of the film. It’s too late to save their business, but it isn’t too late to save Secondo’s soul.

*

Pasta making is one of the great alchemical miracles on this earth. It is, simply, a mixture of one part wet, one part dry, and its yield is something extraordinary. One part viscous, one part powder. In the North of Italy, pasta is usually made from flour and water. In the south, water is replaced with egg. Tucci’s family is from Calabria, the southernmost region in Italy (the toe of the boot), so his family’s pasta recipes yield soft, yellow dough.

Much of Big Night is a search for a way for the brothers to meld together, and the film finds it in pasta. It’s possible that Primo—dense, inflexible Primo—is the flour, and Secondo—much slipperier—is the egg. Permanently aligning Secondo with the egg, in the film’s final scene, he walks into the kitchen and begins to cook, and what he makes is an omelet. The camera hovers in the corner of the room, watching as Secondo cracks and mixes and fries the egg—then cuts it. It is a continuous shot, slow and observational.

Their one employee, the mostly silent Cristiano (Marc Anthony), is already in the room, and Primo arrives shortly thereafter. Secondo has divided the omelet into three pieces “Are you hungry?” Secondo asks his brother. Cristiano moves to give Primo the third plate, but Secondo stops him. “I’ll do it,” he says, reaching to hand his brother the dish—a gesture of compromise and understanding communicated in the most important language: food.

This last scene suggests Secondo’s final transformation, but it also builds on cooking as the mediating force between their conflicting personalities. When the brothers eventually do collaborate on their big meal, their twin timpani, their identical, practically mythical pasta temples, they slap Cristiano’s hand away from poking one of the domes but then pet it themselves, feeling the hot, crusty pasta gentle crackle beneath their fingertips. Again, an overhead shot captures their hands in this reverent, loving gesture, obfuscating which brother is which.

*

When my timpano comes out of the oven, finally, I wiggle the pot up into the air, gently lifting it away from the bubbling mountain of baked pasta. All day, the kitchen has smelled like tomatoes and garlic and salt. As much as I’ve wanted to stay faithful to the Tucci family recipe, I cannot; I’m a vegetarian, so I use Beyond and Impossible meat (minced with breadcrumbs, parsley, garlic, and spices) for the meatballs and the meat ragu. I eschew the salami altogether, and mix mozzarella and ample fresh parmesan with the required provolone. Although I am skeptical about the mandatory hard-boiled eggs, I leave them, but I chop them very small.

The Tucci Cookbook includes a recipe for a vegetarian timpano—a vivacious carnival of vegetables and mozzarella—and I have made this as well. No Big Night research would be complete without the creation of two timpani, as in the film, one for each brother. The vegetarian one—smaller, newer, more desperate to appeal to a modern palette—is for Secondo, and the original is for his brother, Primo. I have never had timpano before, but like the characters in the film, when I take a bite of each, I am floored. I am reborn. I have eaten Italian food—good, homemade, authentic Italian food—all my life, and I have not tasted anything like it before.

Having tasted it now, I understand even more how the dish functions in the film. It is more than a food—there is something holy about it. I too want to put my hands on it, rub it like a saint relic, like the brothers do, but I’m serving it to people, so I resist. There is something about the long day spent making it, and the transcendental experience of eating it, that makes it a vessel by which the brothers can repair their broken bond.

The dish is Primo’s masterpiece but the brothers have made it together from scratch. They have created something impossibly beautiful, something to revere. Rediscovering brotherly communion and a shared language in the act of making pasta leads to a mediating thread between them: an understanding that, even to their conflicting stances, the most important thing about what they do is the food. And food is best when it is a product of love.